Some reenactment specifications suggest a “common heel” for stockings. What do we mean by this?

A common heel has a heel flap, and usually a gusset. The gusset shows above your shoes, so it’s a visible feature. If you look at your 21st century socks, you’ll see a diagonal line in the knit at the heel. This is a short row heel, and is the type of heel that modern circular knitting machines can do easily.

This stocking has a “shaped common heel.” It’s called “shaped” because the back of the heel has a curve. Regular common heels are squared off at the center back instead of shaped.

Another version is called a “Balbriggan heel,” and has shaping at about the ¼ and ¾ mark of the heel flap as well as the center back halfway mark.

These heel terms come from the book Folk Socks by Nancy Bush.

Above is another stocking from the General Carleton, and this one has a Dutch heel. Instead of simply being folded, it has a band of knitting that continues under the heel. It has the side gussets, too. I’m still trying to find the earliest date for a Dutch heel to see if exists by the Rev War era, but the common, shaped common, and Balbriggan heels can be found for that part of the century.

Something to avoid is a slip stitch heel flap, a later technique to make a sturdier heel. It gives a slightly ribbed appearance, and part of it will show above a shoe. It’s popular with modern sock knitters, so if you commission someone to knit a pair of 18th century stockings make sure they don’t do that. For reinforcement, run in the heels instead.

There are a few extant 18thC stockings that do not have a gusset. A stocking which is dated as 1750 (in the DeWitt Wallace museum at Colonial Williamsburg) has decorative clocking, but the structure itself has no gore.

With a similar design and also without a gore is this silk stocking, dated to 1700, which was in the Museum Of Costume & Textiles in Nottingham, England.

Gores allow for a better fit, but were likely skipped in some stockings so they would not interfere with the design. Some stockings are made with a taller gore. Ankle high gores are sufficient for fit, so taller gores also become a design element.

This blobby foot, from the General Carleton, has a short gusset that is not well defined.

This fragment, also in the National Maritime Museum in Poland, is from a Fresian ship that sank in 1791. It would have had no gusset, and the ridge makes it a little bit different from a short row heel. Oops, hey, that’s not supposed to exist in the 18th century! But there it is.

While they’re not all called “common heel,” a gusseted stocking is most likely what you will find in the 18th century. There are variations, so it’s just a matter of having an example that works with the rest of the outfit.

© Carol Kocian and StockingFrameOfMind, 2020. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Carol Kocian and StockingFrameOfMind with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

I am amazed by your research. I find period stockings interesting and have been trying to think of ways to reproduce the look. I have considered using a modern knitting board but I haven’t found one that can make stitches that are fine enough. Now I think I understand the issue. I am very envious of your stocking frame. Well done!

Hi Lori, thank you! Some of the knitting frames (machines) of the time could knit very fine, and denser than what we use today. I continue to hope we can adapt the modern machinery, without breaking it!

Hi!

I love your site! I was just about to give up on finding good resources for machine knit 18th century stockings when I found it. Would you have a few answers to a lost reenactment Swede trying to make sense of this?

I am currently working on a full uniform for a British private ca. 1776 and stockings are next up. I intend to use a modern knitting machine and am now trying to work out the pattern and method. I am struggling with understanding how the part from the gusset and forward is made as I cannot find any side seams or any seam across the sole.

Could it be made from the top and down, then splitting into the middle upper part and the two back pieces, then to the front where it doubles back down and ties back into the upper. Then widens to create the gussets and then ends when it meets the heel parts?

Any help with this would be fantastic!

Hi Carl, thank you for your note! You’re close to the right idea for the way stockings were constructed on frames. I’m planning to write a post of the steps involved and the shapes as they were knit.

A difference with modern knitting machines is that they make a stretchier knit. 18th century stockings were denser and not as stretchy as what we use today. You can get closer by fulling your stockings after you knit them. You’ll need to experiment with the size since fulling will shrink them. I hope to hear more about your progress!

Other things have come in the way so the stocking project has stood still for a while. So I regret to say that I don’t have any progress to share just yet.

Again and again I get impressed with the 18th century(and earlier) mechanics that could compete with the denseness of todays machines (perhaps denseness is not as prioritized nowadays though). I hesitate to start on the actual stockings without understanding the pattern principal so I have not been able to continue since I haven’t found any more leads.

So a post on that would be amazing!

Hi!

I have now finished my shoes, shoebuckles and garters and the next step is the stockings for my uniform.

I am desperately trying to find information on how the toe is constructed on frame knit, late 18th century soldiers’ stockings.

Do you have any idea on where I could find information on that?

Yours

Carl

Hi Carl,

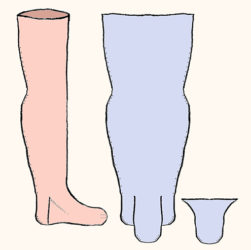

The blue diagram in my logo is typical for a frame knit stocking. The center lobe is the top of the foot, and the shape tapers with decreases as you get to the toe. The smaller piece is the sole, which has the same shape in the toe. The forward edges of both, with the loops, are joined together and bound off, and the sides of the foot are seamed.

Ah!

I think I get it now

Thank you!

Hi!

Now I’ve knit the pieces and find them good enough to stitch them together. On modern construction I see that mattress stitches are used. Is this the case for 18th century ones as well? Or are they just whip stitched together to minimize the bulk of the seam allowance?

I had to look up mattress stitch…. I see that it’s an invisible join, which is not what I see on 18thC machine made. We can see the seams on those.

For the back and side of foot seams, I see chain stitch and also whip stitch. I wonder if the chain stitch is done with a hook, like tambour work. Deborah Pulliam saw a pair, with magnification, where she could tell the chain was done with a needle because the thread did not come out at the same place as it would with a hook. So I assume both types of chain were done, but I don’t know in what proportion. The stocking edges would be placed right sides together and stitched.

One extant pair has a chain stitch on one stocking and whipstitch on the other, perhaps as a repair? Both chain and whipstitch have a bit of flexibility to them, which is good for knits to keep the thread from breaking.

A chain stitch with a hook would go fast. Even with high end silk stockings, you would want a certain amount of production speed.

We also have the join of the sole to the heel flap. In many cases the heel flap is pressed onto the frame and the sole knit from there. I might have an exception, though. My very fine 1830s stocking might have the sole whipstitched to the heel flap, done very carefully to catch each stitch of the sole. I need to get my magnifier, lighting, and camera set up to capture that and see exactly what’s going on.

Hi again!

I finished the stockings in January and forgot to post about it. So here is the final result on Instagram

https://www.instagram.com/p/CtaFns8tOPX/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igshid=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

I could have trusted the stretchiness more and made the foot slightly smaller, but overall I am so happy with the result!

Thank you very much for all your input!

Hello Carol,

I have a few questions about the construction of framework stockings. I am working on recreating stockings with long gores on a modern knitting machine. I have most of it figured out but there is one part that has me stumped. In many examples, at the front edge of the gore there are a few stitches that run perpendicular to the rest of the gore and aren’t part of the instep of the stocking because they are coloured the same as the gore and the whip stiches are between them and the instep. At first I thought they were decreases but the rate of decreasing is too rapid, four or five stitches per row. Do you have any idea how this is achieved? If replying here is inconvenient feel free to email me.

Hello Ollie,

I love hearing about making framework-style stockings! I’m not sure what you mean, would you share a picture?